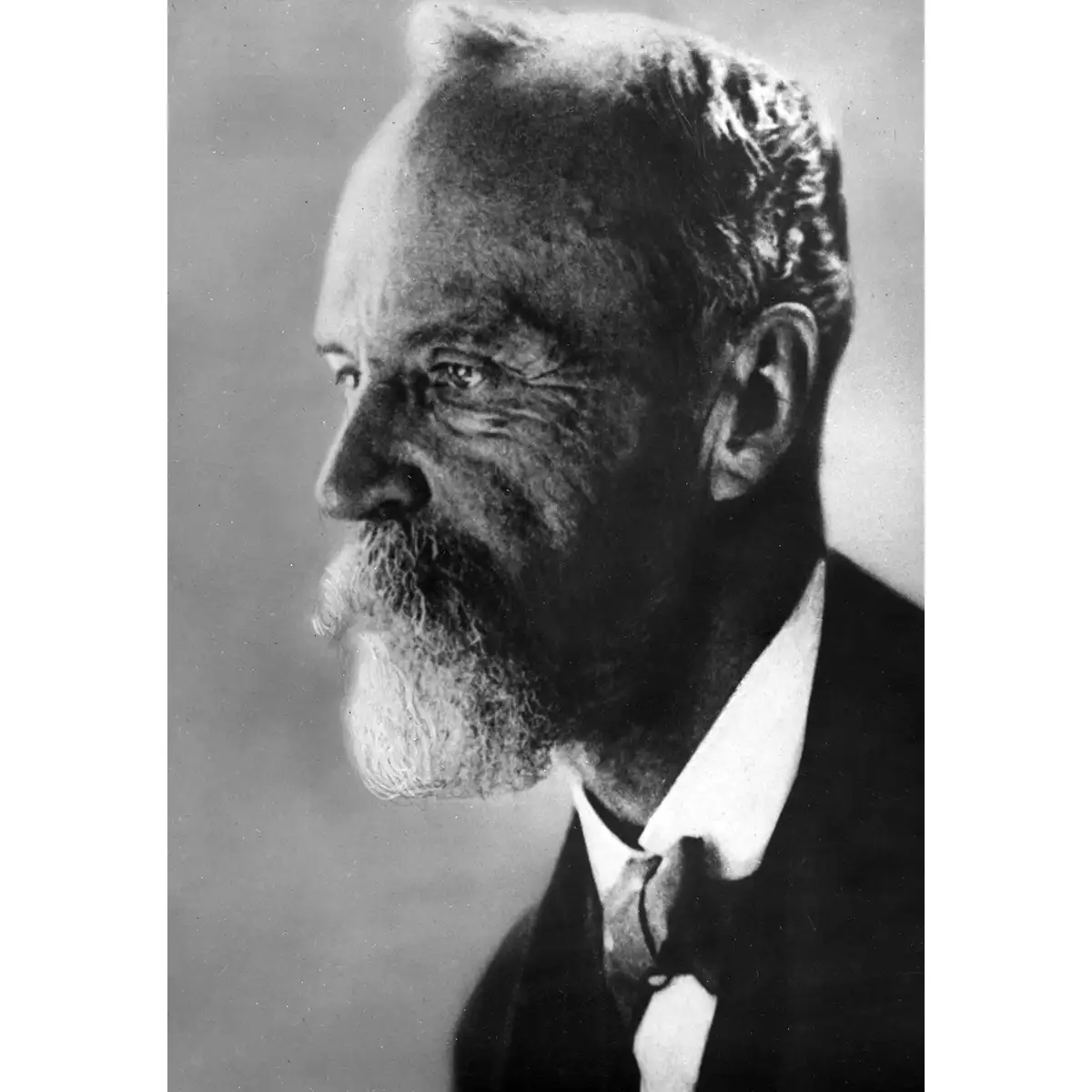

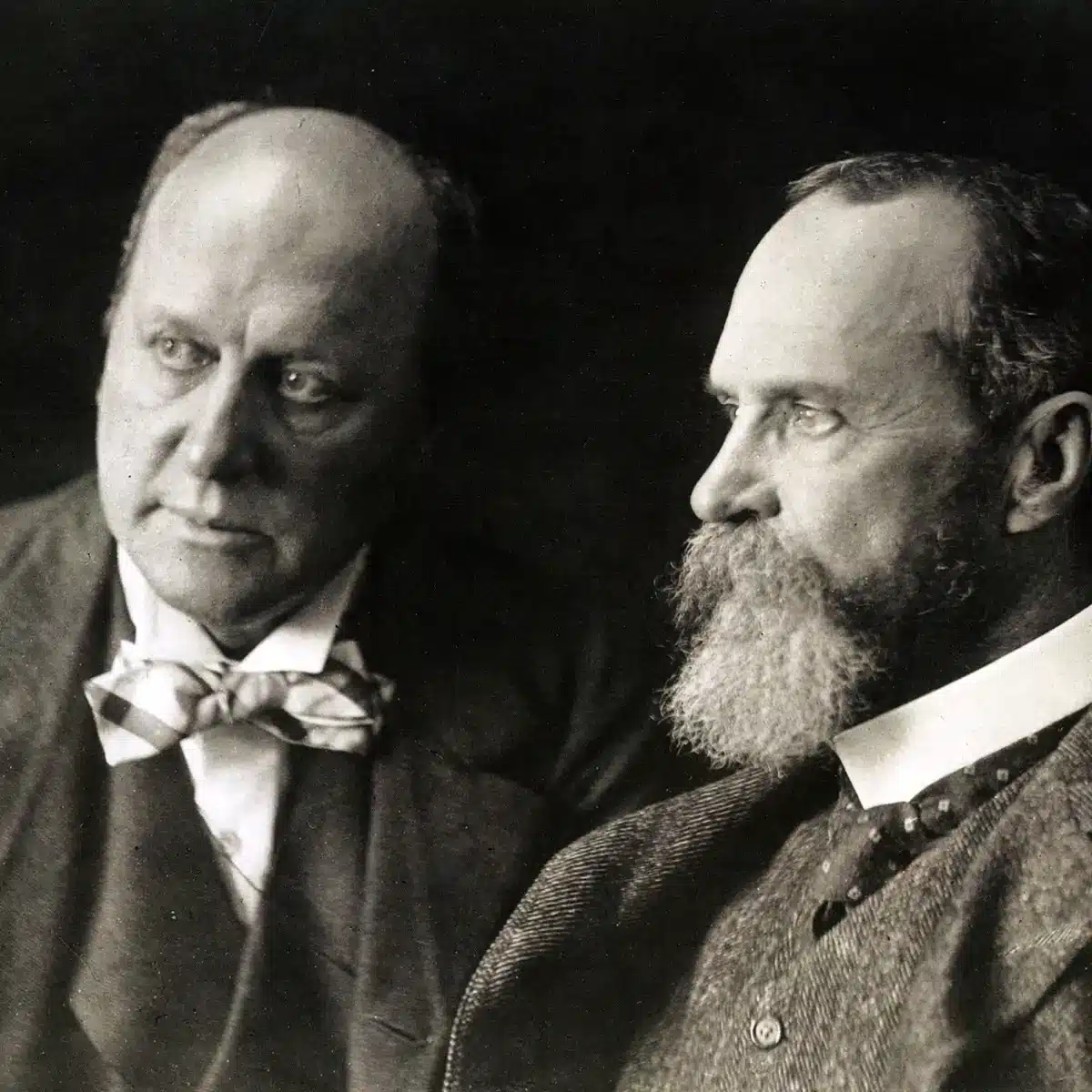

William James zum Todestag (11.1.1842 – 26.8.1910)

Der amerikanische Psychologe und Phlosoph William James, der Bruder von Henry James, veröffentlichte 1900 seine Talks to Teachers and to Students, New York, Holt.

Gerne hat der Alte den Studierenden diesen Text zu lesen gegeben.

William James formuliert in seinem Vortrag schon lange vor der Tätigkeits- und Aktivitätstheorie:

«You may take a horse to the water, but you cannot make him drink; and so you may take a child to the schoolroom, but you cannot make him learn the new things you wish to impart, except by soliciting him in the first instance by something which natively makes him react. He must take the first step himself. He must do something before you can get your purchase on him.» (p. 36)

Gleiches gilt für die Lehrpersonen:

«Children admire a teacher who has skill. What he does seems easy, and they wish to emulate it. It is useless for a dull and devitalized teacher to exhort her pupils to wake up and take an interest. She must first take one herself; then her example is effective, as no exhortation can possibly be.» (p. 48)

Zu Beginn des Generalisierungsprozesses der öffentlichen Schulen schreibt William James:

«Every school has its tone, moral and intellectual. (p. 50)

Daran muss natürlich konstant zusammen gedacht und gearbeitet werden. Die Schule gehört allen Beteiligten mit ihren eigenen Interessen, Beziehungen und Sammlungen (Bücher, Bilder, Texte, Notizen, Skizzen, …):

«In education, the instinct of ownership is fundamental, and can be appealed to in many ways. In the house, training in order and neatness begins with the arrangement of the child’s own personal possessions. In the school, ownership is particularly important in connection with one of its special forms of activity, the collecting impulse.» (p. 53)

Der Alte liebt besonders folgende Passage, in der William James auf die Notwendigkeit der Präsenz des wahren Lebens, der Anekdoten, der Experimente, der ästhetischen Gestaltungen und der Geschichten für die Gestaltung authentischer Lernprozesse hinweist:

«Living things, then, moving things, or things that savor of danger or of blood, that have a dramatic quality, – these are the objects natively interesting to childhood, to the exclusion of almost everything else; and the teacher of young children, until more artificial interests have grown up, will keep in touch with her pupils by constant appeal to such matters as these. Instruction must be carried on objectively, experimentally, anecdoctically. The blackboard-drawing and story-telling must constantly come in.» (p. 56)

Das persönliche Leben und Erleben jedes Kindes ist der Grundstock seiner Bildung und Lernprozesse:

«(…) relation to his personal life. From all these facts there emerges a very simple abstract programme for the teacher to follow in keeping the attention of the child: Begin with the line of his native interests, and offer him objects that have some immediate connection with these.» (p. 57)

Bewegende Worte (schon um 1900!) findet William James, wenn es um die Messbarkeit schulischen Lernens geht:

«(…) man is too complex a being for light to be thrown on his real efficiency by measuring any one mental faculty taken apart from its consensus in the working whole. Such an exercise as this, dealing with incoherent and insipid objects, with no logical connection with each other, or practical significance outside of the ‚test,‘ is an exercise the like of which in real life we are hardly ever called upon to perform. In real life, our memory is always used in the service of some interest: we remember things which we care for or which are associated with things we care for; and the child who stands at the bottom of the scale thus experimentally established might, by dint of the strength of his passion for a subject, and in consequence of the logical association into which he weaves the actual materials of his experience, be a very effective memorizer indeed, and do his school-tasks on the whole much better than an immediate parrot who might stand at the top of the ’scientifically accurate‘ list. (…) No elementary measurement, capable of being performed in a laboratory, can throw any light on the actual efficiency of the subject; for the vital thing about him, his emotional and moral energy and doggedness, can be measured by no single experiment, and becomes known only by the total results in the long run.» (pp. 58, 71)

Vertrauen wir am besten dem denkenden Kind, so William James.

Das erinnert den Alten daran, dass er mehrmals in seiner Karriere bei Vorträgen und Konferenzen vor schulischen Bürokraten und apathischen Lehrpersonen mit folgendem Satz geendet hat: „Don´t forget! Listen to the kids!“

William James sagt es viel besser:

«(…) the total impression which a perceptive teacher will get of the pupil’s condition, as indicated by his general temper and manner, by the listlessness or alertness, by the ease or painfulness with which his school work is done, will be of much more value than those unreal experimental tests, those pedantic elementary measurements of fatigue, memory, association, and attention, etc., which are urged upon us as the only basis of a genuinely scientific pedagogy. Such measurements can give us useful information only when we combine them with observations made without brass instruments, upon the total demeanor of the measured individual, by teachers with eyes in their heads and common sense, and some feeling for the concrete facts of human nature in their hearts. (…) Be patient, then, and sympathetic with the type of mind that cuts a poor figure in examinations. It may, in the long examination which life sets us, come out in the end in better shape than the glib and ready reproducer, its passions being deeper, its purposes more worthy, its combining power less commonplace, and its total mental output consequently more important. (…) the art of remembering is the art of thinking; (…) when we wish to fix a new thing in either our own mind or a pupil’s, our conscious effort should not be so much to impress and retain it as to connect it with something else already there. The connecting is the thinking; and, if we attend clearly to the connection, the connected thing will certainly be likely to remain within recall.»

0 Kommentare